- Ethical principles applied to resuscitation

Involving patients

People have ethical and legal rights to be involved in decisions that relate to them and if the patient has capacity their views should be sought unless there is a clearly justifiable reason to indicate otherwise.

It is not necessary to initiate discussion about CPR with every patient, for example if there is no reason to expect cardiac arrest to occur, or if the patient is in the final stage of an irreversible illness in which CPR would be inappropriate as it would offer no benefit.

Involving relatives

It is good practice to involve relatives in decisions although they have no legal status in terms of actual decision-making.

A patient with capacity should give their consent before involving the family in a DNAR discussion. Refusal from a patient with capacity to allow information to be disclosed to relatives must be respected.

Lack of capacity

If patients who lack capacity have previously appointed a welfare attorney with power to make such decisions on their behalf, that person must be consulted when a decision has to be made balancing the risks and burdens of CPR.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005, which applies in England and Wales requires appointment of an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) to act on behalf of the patient who lacks capacity. However, when decisions have to be made in an emergency, there may not be time to appoint and contact an IMCA and decisions must be made in the patient’s best interests, and the basis for such decisions documented clearly and fully.

Grey areas

Inevitably, judgments will have to be made, and there will be grey areas where subjective opinions are required in patients with comorbidity such as heart failure, chronic respiratory disease, asphyxia, major trauma, head injury and neurological disease.

The age of the patient may feature in the decision but is only a relatively weak independent predictor of outcome; however, the elderly commonly have significant comorbidity, which influences outcome.

When differences of opinion occur between the healthcare team and the patient or their representatives these can usually be resolved with careful discussion and explanation, or if necessary by obtaining a second clinical opinion.

When to stop CPR

The decision to stop CPR can be made when it is clear that continuing CPR will not be successful.

In general, CPR should be continued as long as a shockable rhythm or other reversible cause for cardiac arrest persists. It is generally accepted that asystole for more than 20 minutes in the absence of a reversible cause, and with all advanced life support measures in place, is unlikely to respond to further CPR and is a reasonable basis for stopping CPR.

In out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, CPR will be started unless:

- There is a valid advance decision refusing it, or

- A valid DNAR order, or

- It is clear that CPR would be futile

References

- See chapter 16 of the ALS manual for further reading about decisions relating to resuscitation

- Joint statement about decisions relating to cardiopulmonary resuscitation published by the British Medical Association (BMA), the Resuscitation Council (UK) and the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) http://www.resus.org.uk/pages/dnar.htm

- The Resuscitation Council (UK) guidance on the legal status of those who attempt resuscitation http://www.resus.org.uk/pages/legal.htm

- The General Medical Council (GMC) guidance on treatment and care towards the end of life: good practice in decision making www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/end_of_life_care.asp

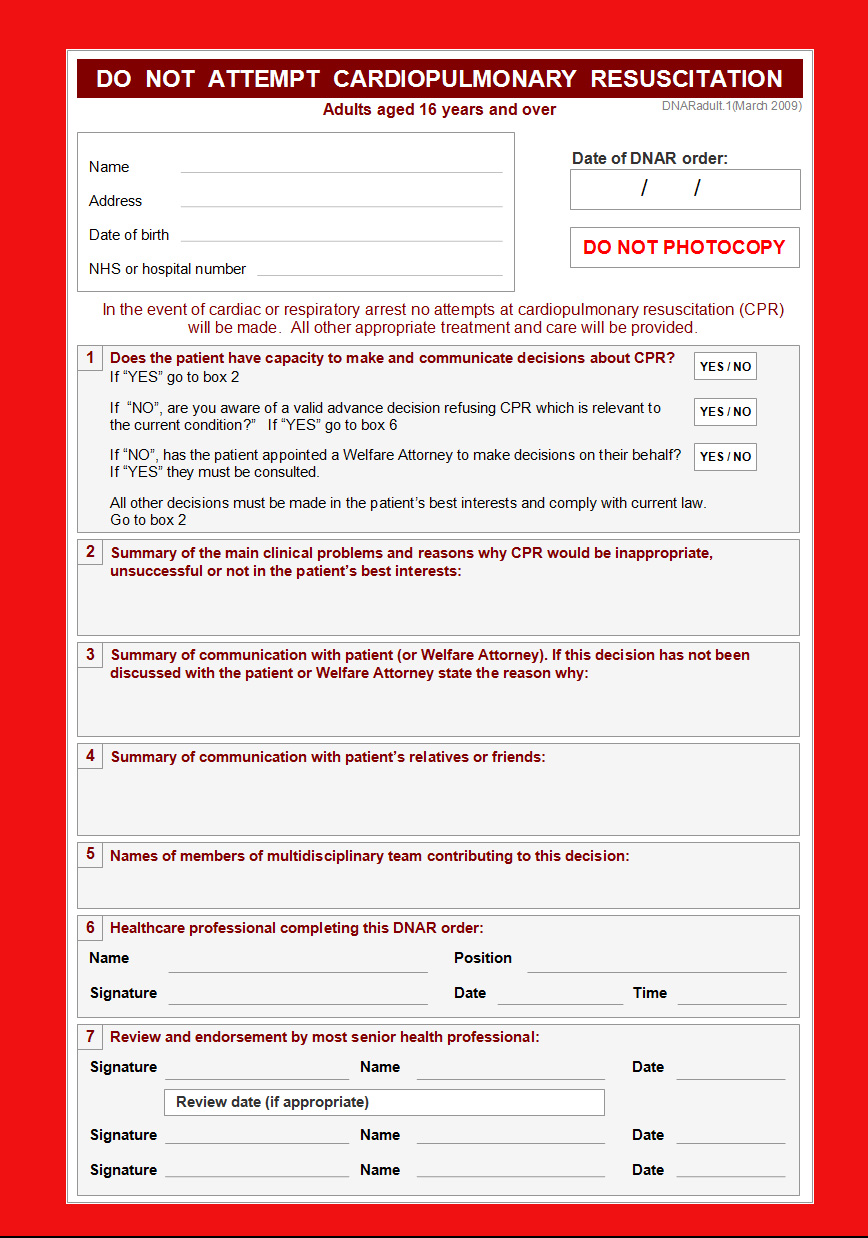

Essentials: Model DNAR forms