Recognising and treating acute coronary syndromes

Acute Coronary Syndromes

Learning outcomes

- To understand the clinical spectrum of coronary disease

- To recognise different presentations of the disease process

- To be aware of the different treatment options for each clinical presentation

Acute coronary syndromes

Spectrum of clinical presentation caused by:

- Atherosclerotic plaque rupture

- Smooth muscle constriction

- Thrombus formation

Fissured plaque

Acute coronary syndromes

Clinical syndromes caused by the same disease process:

- Unstable angina

- Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Stable angina

Pain or discomfort from myocardial ischaemia:

- Tightness/ache usually across chest

- May radiate to throat/arms/back/epigastrium

- Consistently provoked by exercise

- Settles when exercise stops

NOT an acute coronary syndrome.

Unstable angina

- Angina on exertion with increasing frequency over a few days, provoked by less exertion

or - Angina occurring recurrently and unpredictably - not specific to exercise

or - Unprovoked and prolonged episode of chest pain

- ECG may be normal

- ST segment depression suggests high risk

- No troponin release

- Cardiac enzymes usually normal

Acute ST depression

Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)

- Symptoms suggesting acute MI

- Non-specific ECG abnormalities

- ST segment depression

- T wave inversion

- Troponin release

- Usually elevated cardiac enzymes

- e.g. creatine kinase (CK)

NSTEMI

ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

- Symptoms suggesting acute MI

- Acute ST-segment-elevation

- Q waves likely to develop

- Troponin release

- Usually elevated cardiac enzymes (e.g. CK)

- Early effective treatment may limit myocardial damage and prevent Q wave development

Anterolateral STEMI

Immediate treatment for all acute coronary syndromes

- ABCDE approach

- Aspirin 300 mg orally (crush/chew)

- Nitrate (GTN spray or tablet)

- Oxygen if appropriate

- Morphine (or diamorphine)

Unstable angina and NSTEMI

- Anti-thrombotic

- Aspirin

- Clopidogrel or prasugrel

- LMW heparin or fondaparinux

- if very high risk: glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor

- Pain relief

- Nitrate

- Morphine

- Oxygen if appropriate

- Myocardial protection

- Beta blocker

- coronary angiography/PCI in most patients

STEMI (or acute MI with new LBBB)

Emergency reperfusion therapy:

- Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

- Fibrinolytic therapy

Avoid delay – “Time is muscle”.

Access to emergency reperfusion

Left bundle branch block

Absolute contraindications to fibrinolytic therapy

- Previous haemorrhagic stroke

- Other stroke or CVA within six months

- CNS damage or neoplasm

- Active internal bleeding

- Aortic dissection

- Recent major surgery or trauma

- Known bleeding disorder

STEMI – further management

- Anti-thrombotic therapy

- Beta blocker

- ACE inhibitor

- Coronary angiography and reperfusion strategies e.g. PCI

Summary

- Recognise the different presentations

- Use ABCDE approach

- Start appropriate immediate treatment

- Arrange emergency reperfusion therapy when appropriate

- Identify other high-risk patients for further investigation and treatment

Advanced Life Support course

e-lecture

All rights reserved

© Resuscitation Council (UK) 2011

1. In this session we are going to consider acute coronary syndromes.

Acute coronary syndromes are important because coronary artery disease is the commonest cause of cardiac arrest and sudden death in many parts of the world, including the UK. Many of these events occur during an acute coronary syndrome.

It is therefore very important for an ALS provider to be able to recognise an acute coronary syndrome. We need to carefully assess these patients to ensure that they receive immediate and appropriate treatment to reduce their risk of suffering cardiac arrest or sudden death.

2. The learning outcomes expected from this session are the following:

- firstly, that you understand the clinical spectrum of coronary disease – from stable angina all the way to large heart attacks

- secondly, that you are able to recognise the different ways in which coronary disease may present

- and finally, that you are aware of the different treatment options available

3. The underlying problem in acute coronary syndromes is coronary artery disease in which plaques filled with cholesterol build up in the lining of these arteries.

Acute coronary syndromes are caused by rupture of the inner surface of one of these plaques.

Blood then enters the plaque causing it to swell and protrude into the artery. Smooth muscle in the wall of the artery may constrict, causing further narrowing of the artery and further restriction of the blood supply to the heart muscle that it supplies. Finally, the chemical effect of the injury to the wall of the blood vessel stimulates thrombus formation and if this develops into a large clot, it may cause further narrowing of the artery or may block it completely.

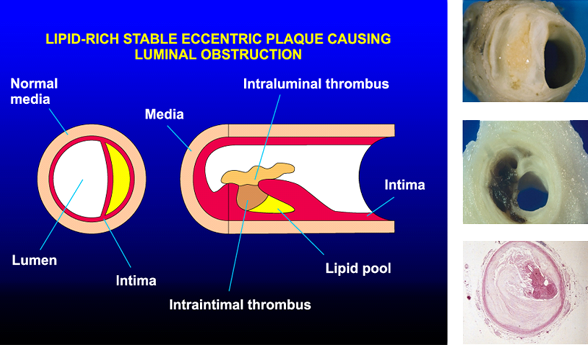

4. These pictures illustrate these processes.

The diagram on the left illustrates a cross-section of the coronary artery containing a cholesterol-filled plaque that is only reducing the diameter of the vessel by about a third. It is unlikely to be causing significant reduction of the blood flow to the heart and unlikely to be causing any symptoms.

The diagram in the centre shows a longitudinal section through a coronary artery in which one of these plaques has ruptured. Blood has entered the plaque and started to clot, and there has been further thrombus formation on the surface of the plaque. The swollen plaque and thrombus together have reduced the diameter of the lumen to less than a third of its original natural diameter.

The three pathological specimens on the right show firstly, a large atheromatous plaque containing cholesterol which is causing a major reduction in the diameter of the artery. A plaque of this size would certainly reduce the blood flow to the heart muscle that it supplies. The yellow colour is the liquid fat within the plaque, most of which is cholesterol.

The middle picture shows another large plaque that has ruptured. The black staining shows the presence of blood mixed with the cholesterol in the plaque.

The histology slide at the bottom shows another artery that not only has a large atheromatous plaque that greatly reduces the lumen, but in this patient the darker colouring within the lumen indicates that the artery has been completely blocked by thrombus.

5. Acute coronary syndromes are the clinical presentation of this pathological process.

Acute coronary syndromes present along a spectrum which is subdivided into the following:

- unstable angina

- non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- ST-elevation myocardial infarction

We will go on shortly to consider how to recognise these and to understand why and how the treatment of each may differ.

6. But before we focus more closely at the presentation of acute coronary syndromes it helps to understand the difference between stable and unstable angina.

The coronary arteries are the fuel pipes to the heart. When people exercise, their hearts need more fuel. In other words the exercising heart muscle will need an increase in the flow of blood carrying oxygen and glucose. When the coronary arteries are substantially narrowed by plaques of atheroma they do not allow an increase in blood flow to the heart muscle. When the myocardium cannot get the blood supply that it needs for the work that it is doing, it becomes ischaemic.

Stable angina is the discomfort or pain felt by patients as a result of the cardiac ischaemia as they exercise.

The discomfort usually presents as an ache or tightness in the chest. It may radiate up to the throat, arms, back or upper abdomen. It sometimes occurs in one or more of these areas without involving the chest.

It is important to note that stable angina is provoked consistently by exercise and settles when exercise stops. The amount of exercise needed to bring it on can vary from one time to another and in particular it may come on much earlier when people take exercise after a meal or in a cold environment.

However, stable angina is predictable and reproducible.

It is this consistent provocation by exercise, without rapid worsening over time that defines the situation as stable angina and not an acute coronary syndrome.

7. In contrast unstable angina which is an acute coronary syndrome can present in one of three ways.

Firstly, the angina may still be provoked by exercise, but occurs with increasing frequency over a matter of hours or days and tends to be provoked by progressively less exertion as it progresses. This is sometimes referred to as crescendo angina.

Secondly, unstable angina can present with angina that occurs recurrently at rest but usually resolves after a few minutes on each occasion.

Thirdly, unstable angina can present as a single episode of prolonged chest pain (usually raising suspicion of myocardial infarction).

Unstable angina represents a situation where previously stable symptoms have become unpredictable and unstable. These patients are not having a heart attack (known as a myocardial infarction) but are at significant risk of progressing to one.

In all of these situations, the ECG may be normal. However if the ECG shows ST segment depression, this suggests a high risk of progression to myocardial infarction and an increased risk of death.

In unstable angina there is no damage to the heart muscle, so blood tests will not detect any troponin release.

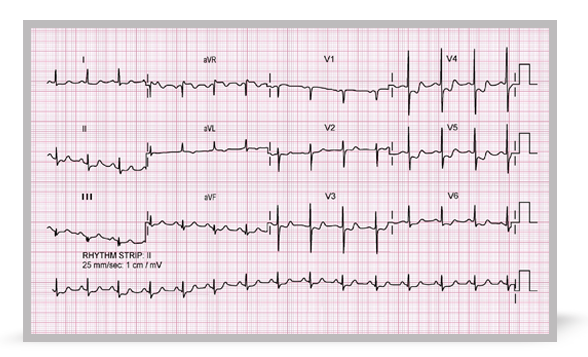

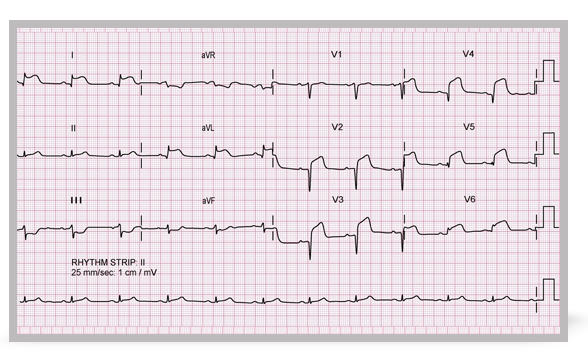

8. This is an ECG from a patient with an acute coronary syndrome. It shows the type of ST segment depression that indicates high risk in this setting.

This ECG demonstrates ST depression. The ST depression is most prominent in the anterolateral chest leads V3 to V6. If you look carefully, you will also see some ST depression in the limb leads I and II as well as T wave inversion in aVL.

It is not possible from the ECG alone to distinguish between unstable angina and a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, and that is determined by the presence or absence of troponin release.

9. Although unstable angina is part of the spectrum of acute coronary syndromes, it is not myocardial infarction as there is no evidence of myocardial necrosis. Non-ST-elevation and ST-elevation MIs are acute coronary syndromes, presenting typically with chest pain and evidence of troponin release on blood testing. Troponin release indicates that there has been some myocardial cell death and is used to differentiate unstable angina from non-ST-elevation and ST-elevation myocardial infarctions. The differentiation between non-ST-elevation MI and ST-elevation MI is based on the ECG findings.

So, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction typically presents with prolonged angina-like chest, throat or arm pain which may be associated with feeling clammy and nauseous. The pain usually lasts for 20 minutes or longer. Often there will be associated ECG changes such as ST depression or T wave inversion, but occasionally the ECG may be normal, at least in the early stages. However, there will be troponin release.

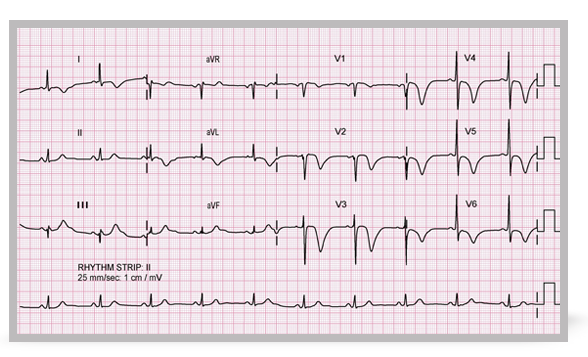

10. This ECG was recorded from a patient who experienced chest pain that was severe and prolonged. There is deep T wave inversion in leads V2 to V6 and in the lateral limb leads I and aVL.

With the history clearly suggesting myocardial infarction, these abnormalities indicate a high probability of a severe narrowing in one of the major coronary arteries.

Once again the diagnosis of non-ST-elevation infarction is made not purely from the ECG but from a typical history coupled with troponin release. The pattern of ECG abnormality simply serves to highlight that the patient is at risk and that they require prompt and effective treatment.

11. When an acute myocardial infarct is accompanied by ST segment elevation, this usually implies complete occlusion of the affected coronary artery. It is important to differentiate between non-ST-elevation MIs and ST-elevation MIs because the treatment options are different.

Both types of myocardial infarct usually present with typical symptoms as discussed and both are accompanied by troponin release. The difference with ST-elevation MIs is seen in the ECG. Acute elevation of the ST segments in the leads overlying the area of infarction is usually present at an early stage. This is likely to be followed by the development of pathological Q waves (representing myocardial death) within these leads.

Patients with an acute coronary syndrome presenting with new LBBB on their ECG fall into the same category as patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction and should be treated similarly.

Recognition of ST-elevation MI and early effective treatment of it may limit the amount of myocardial damage and, by so doing, prevent the development of Q waves in the ECG and reduce the risk of complications including heart failure and death.

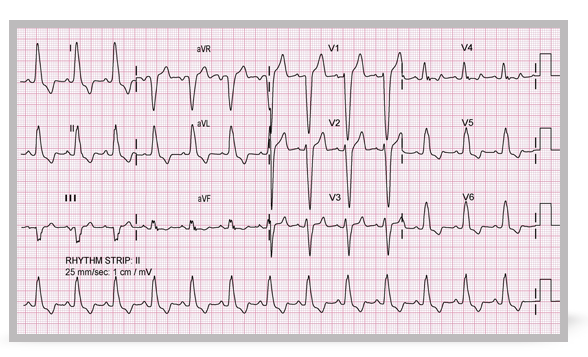

12. Here is an example of an acute anterolateral ST-elevation infarction.

Q waves have already developed in the anterior chest leads but there is ST segment elevation from V2 to V6 and this is seen also in the lateral limb leads I and AVL.

The Q waves indicate that myocardial damage has already occurred but nevertheless if appropriate treatment is given early enough further damage may be prevented.

13. As we are emphasising throughout this course, our clinical assessment of acutely unwell patients should use the structured ABCDE approach.

Unless this identifies a need for other immediate action or there are contra-indications, we should do the following for all patients who we suspect of having an acute coronary syndrome:

- a loading dose of aspirin should be given to start to protect against new thrombus formation

- also, we should give sublingual GTN, in either spray or tablet form

- we should consider giving oxygen unless there is a clear contra-indication and once it is started, the concentration should be adjusted on the basis of oxygen saturation

- and, of course, it is important to provide effective pain relief using morphine or diamorphine

14. In most patients with unstable angina or a non-ST-elevation MI, the coronary artery that has caused the problem has not yet blocked. Therefore, we need to give drug treatment to prevent further thrombus formation that might block the artery.

In addition to aspirin we give clopidogrel or prasugrel tablets and we give injections of low molecular weight heparin or fondaparinux unless there are clear contra-indications such as active bleeding.

In very high risk patients we may also give a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (via an infusion) whilst preparing the patient for very urgent coronary angiography with a view to probable stent insertion.

As with all patients with acute coronary syndromes, it is important to relieve pain using nitrates which may be given sublingually or can be given over a longer period as an infusion. In addition the use of morphine or diamorphine is appropriate in any patient whose pain does not respond promptly to sublingual nitrate. Oxygen is given as we have already described.

In addition, in the absence of any contra-indication we should consider trying to provide myocardial protection by starting a beta blocking drug.

Once these patients have been established on treatment, it is very important to reassess them at frequent intervals. Further action may be needed if patients go on to exhibit high risk behaviour such as persistent or recurrent chest pain or new ECG abnormality.

Coronary angiography with a view to possible percutaneous coronary intervention should be considered in all these patients during the same hospital admission. There will be a few in whom the potential benefit from invasive assessment and treatment is unlikely to outweigh the risk, but for most patients coronary angiography will be appropriate. However, this does not have to be done as an emergency unless the patient is exhibiting on-going high-risk behaviour.

15. In complete contrast is the patient with an ST-elevation myocardial infarction or new left bundle branch block due to acute myocardial infarction. The majority of patients who present with this condition have an occluded coronary artery and unless it is re-opened, achieving reperfusion of the heart muscle that it supplied, further muscle damage will occur. This puts the patient at an increased risk of cardiac arrest and death.

After initial assessment using the ABCDE approach and after administration of appropriate medical treatment (including aspirin, other anti-thrombotic agents, nitrate, oxygen and analgesia as required) the priority is to re-open the coronary artery that has caused and is continuing to cause myocardial damage.

The most reliable way of re-opening an occluded coronary artery in this situation is by percutaneous coronary intervention so this is currently the recommended approach in the majority of these patients.

When PCI is not available on an emergency basis in the locality, an alternative approach would be to use fibrinolytic therapy which will re-open the artery in a proportion of patients and then to transport the patient to a hospital where PCI can be performed later if necessary.

The important thing is to re-open the artery as quickly as possible. The greater the delay, the more myocardium will be damaged irreversibly.

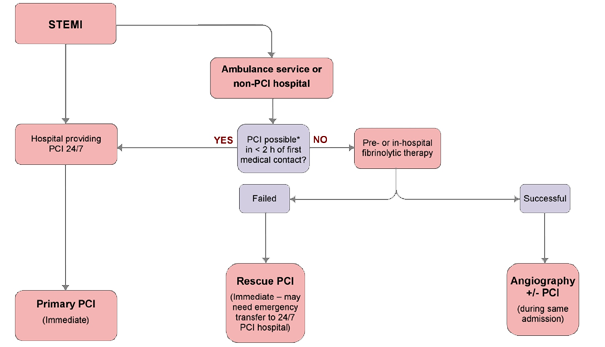

16. This algorithm shows the pathway that is recommended for patients with ST elevation infarction.

If they present to a hospital that provides round-the-clock PCI, they should be taken to the catheter laboratory immediately with a view to re-opening the occluded artery as soon as possible.

When the diagnosis is made in the community and an ambulance is called or when the diagnosis is made at a hospital that does not provide primary PCI, if it is possible to achieve PCI within two hours of that patient’s first call for help with chest pain, they should be taken to the appropriate primary PCI hospital.

If no such facility is available within two hours, they should receive fibrinolytic therapy at the earliest possible time, either pre-hospital by the ambulance service or in hospital if the diagnosis has not been made before their arrival.

When fibrinolytic therapy appears to have failed because of continuing or recurrent chest pain or because of persistent ST segment elevation on the ECG, they should then be transferred as an emergency to a primary PCI centre for coronary angiography with a view to stent insertion if possible. This situation is referred to as rescue PCI.

If the clinical and ECG response to fibrinolytic therapy suggests that it has been successful in re-opening the artery the patient should continue medication to protect the heart and to minimise the risk of re-occlusion of the artery. In the majority of these patients, however, it is still appropriate to consider transfer for coronary angiography before they leave hospital.

If there is any uncertainty about whether a patient should receive PCI or fibrinolytic therapy or whether a patient requires reperfusion therapy at all, then it is always best to discuss the decision with the cardiology team at the local PCI centre.

17. This ECG shows a typical example of left bundle branch block and is simply to remind us that when this occurs as a new development in someone presenting with myocardial infarction they should be treated in the same way as a patient with an ST-elevation infarct. So as an ALS provider it is important that you can recognise this typical pattern of complete left bundle branch block.

We mentioned earlier that primary PCI is the most reliable way of re-opening an occluded coronary artery.

Another advantage of primary PCI over fibrinolytic therapy is that it is associated with a lower risk of major bleeding, and this list shows the absolute contra-indications to fibrinolytic therapy because of the risk of bleeding. If people with these problems present with an ST-elevation myocardial infarction, they will need careful assessment on an individual basis in order to plan their treatment and consider whether or not it is appropriate to transfer them immediately for primary PCI.

It will be important also to consider carefully the relative risks and benefits of each of the anti-thrombotic agents that we would otherwise recommend and to plan all other aspects of their treatment very carefully.

19. For patients who have been treated for ST-elevation myocardial infarction we need to consider what on-going treatment they should receive to minimise future risk.

Having re-opened a blocked coronary artery, it is important to maintain anti-thrombotic therapy to keep it open.

There is good evidence that in the absence of any clear contra-indication such as asthma the use of a beta blocking drug will help to reduce the risk of further myocardial infarction and of death. In addition, the use of an ACE inhibitor will help to protect against deterioration in left ventricular function that in turn may place the patient at risk of heart failure and of sudden death.

We have already mentioned that for those patients who have not already undergone coronary angiography and primary PCI, an angiogram and the need for reperfusion would be appropriate in the majority of patients whose initial treatment was with fibrinolytic therapy.

20. To summarise, this session has described the common different presentations of coronary artery disease, emphasising the difference between stable and unstable angina and the different types of acute coronary syndrome.

We have emphasised the importance of maintaining the structured ABCDE approach to clinical assessment of any acute problem including acute coronary syndromes.

We have considered the immediate treatments that (unless contra-indicated) should be given to all patients with acute coronary syndromes. In addition, for patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction we have emphasised the importance of re-opening the blocked coronary artery at the earliest possible moment as safely and effectively as possible. For most people this will mean primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Finally, whilst many patients with acute coronary syndromes will undergo coronary angiography as part of their assessment at some stage, we have recognised that some high-risk features can be identified, such as persistent or recurrent pain and certain ECG features that will help to identify some patients who are at higher risk and who should therefore be considered for coronary angiography sooner rather than later.

Dr Rani Robson is a member of the Resuscitation Council (UK) ALS Subcommittee. She contributed to writing the 2010 Guidelines for the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR). She is a Specialist Registrar in Cardiology at the Bristol Heart Institute. (2011).